Theory often takes a back seat to practice in the field of web design—after all, it’s hard enough to keep up with the latest acronyms without trying to carve out time for navel gazing about the profession. As a result, innovation in the way we think about our creations has lagged behind the breakneck pace of change in the technologies we use to create them. Consider, for example, our craft’s foundational metaphor of “information architecture.” Since at least Richard Saul Wurman’s 1996 book Information Architects, architecture has been the primary metaphor for how “those who build websites” think about what we do. By adding a new metaphor to our theoretical toolboxes, we can gain a richer, more nuanced understanding of the way that we inhabit cyberspace. This enhanced apprehension of the medium should enable us to create websites that better serve our users.

Article Continues Below

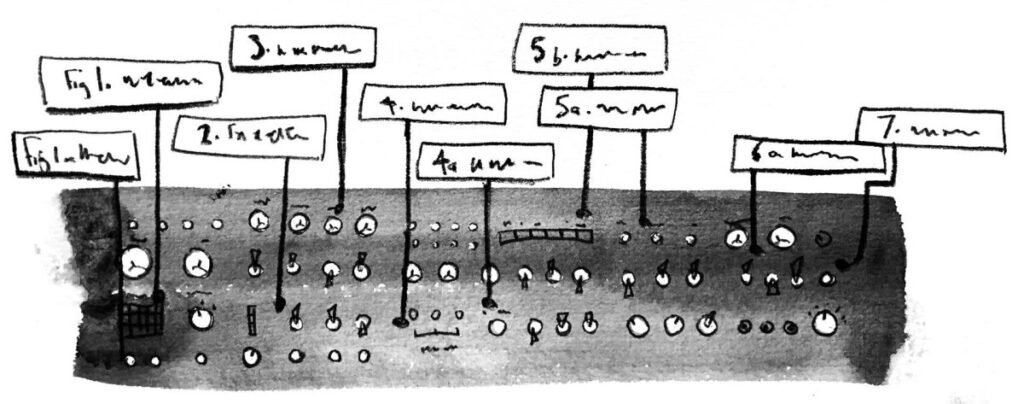

At the law school where I work, I was hired in large part to lead a redesign of our nearly four-year-old site, which contains around 6,000 pages. As I delve into this overgrown information jungle, I don’t feel like an architect—I feel like an explorer, an adventurer into the darkest recesses of institutional memory. I am charting abandoned territory, noting the relative locations of long-deserted pages, the promising paths that lead to deadends, and the sheer cliffs of 404 pages. But I am also mapping the school itself, though not physically: I am mapping the intellectual histories of our professors, the aspirations of our students, and the ideas, people, and capital that flow in and out of the institution. This map will, in turn, become the blueprint for the architectural portion of the project—laying the groundwork for the new temple that will rise from the ruins of the old site.

Consider cartography as a metaphor#section2

I suggest, therefore, that the art of cartography might fruitfully be used alongside architecture. This might sound like an odd suggestion, since at first glance, cartography appears to be nearly the opposite of architecture. Common sense tells us that an architect begins with an abstraction—a blueprint—and creates from that abstraction a concrete structure existing in physical space. The cartographer, on the other hand, starts with concrete structures existing in physical space and creates from that an abstraction: a map.

For years, most of us have thought of building a website as being more like the former. We sketch out tree hierarchies and wireframes, and use them as the blueprints for the creation not of a physical structure, but an informational structure (and sometimes, if we’re feeling generous to our users, we’ll re-abstract those structures into “sitemaps” to aid their navigation around the site). What we often forget is that the blueprints from which we construct a site are themselves maps of processes and flows that already exist, from verbal dialogues to the exchange of money for goods and services.

What Lefebvre knew about space and social interaction#section3

The conception of web designer as information architect depends upon a vision of cyberspace not unlike the vision of physical space held by René Descartes (1596-1650). To him, and to most of Western civilization for hundreds of years, space was a void, a preexisting grid which remains empty until points are identified and paths plotted upon it. (Think of the digital plains depicted in the movie Tron.)

In the 1970s, however, Henri Lefebvre’s work The Production of Space turned this view on its head, arguing that space is produced through the enactment of social relations. Space, according to Lefebvre, is created by the flows and movements of relational networks—such as capital, power, and information—in, across, and through a given physical area. A building, in Lefebvre’s reading, is a map of the interactions of the people who inhabit it; an architect is not a builder in an otherwise empty wilderness, but an observer, chronicler, and shaper of the networks that exist around her—in short, a map maker. Websites informed by a Lefebvrian conception of cyberspace rather than a Cartesian one would provide truly user-centered design, by recognizing that it is the users themselves whose actions produce the website; the web designer merely facilitates that creation.

Websites as memory dwellings#section4

For a different angle on how cartography might inform web design, we may look to a source even more unlikely than French philosophers: the rhetoricians of ancient Rome. Like most websites, which aim to convince the user to take some sort of action—buy this product, apply to this school, hire this individual, post a comment—the goal of the rhetorician was persuasion. To the rhetorician Quintilian (35-100 CE), the key to persuasion was memory: the rhetorician had to be able to access quickly and accurately “the store of precedents, laws, rulings, sayings and facts which the orator must possess in abundance and which he must always hold ready for immediate use,” or his attempts at persuasion would be in vain. (Institutio Oratoria, Book XI, Chapter 2)

In order to do so, Quintilian suggests a remarkable mnemonic device: the orator should imagine “a place…of the largest possible extent and characterised by the utmost possible variety, such as a spacious house divided into a number of rooms” (ibid.). In each room he should place an object or set of objects associated in some way with an individual fact or argument. Each room can then be visited in turn in order to bring to mind the concepts associated with each object. Memory (and thus, according to Quintilian, persuasion) is reliant upon this act of spatial imagination:

We require, therefore, places, real or imaginary, and images or symbols, which we must, of course, invent for ourselves. By images I mean the words by which we distinguish the things which we have to learn by heart: in fact, as Cicero says, we use ‘places like wax tablets and symbols in lieu of letters.’ (ibid.)

In this formulation, the rhetorician is both architect (the builder of a memory dwelling) and cartographer (the memory dwelling is to actual memory as a map is to the territory it depicts). His imagined building, in other words, is also a map.

Mapping memory collectively: no more digital monuments#section5

The redesign of my law school’s website is not unlike the creation of a rhetorician’s memory dwelling. Built from the collective memory of our past and current students and faculty, the website is an abstraction—a map—of that memory, created to persuade prospective students to apply, current students to collaborate, and alumni to remain engaged with the school. The crucial difference is that the law school’s memory dwelling, unlike Quintilian’s, has more than one inhabitant. Our users, by continually adding to and altering the school’s collective memory, contribute to the production of the website—the abstraction of that memory. Instead of imposing an architecture upon users from above, we should use the flow of their interactions with the site and with each other to determine the form of this memory map.

Just as Lefebvre leads us to see built spaces not as the expressions of a single architect, but rather as the production of the wide variety of human interactions that occur within them, so websites created by cartographers would cease being grand edifices of unidirectional communication and become instead the collective product of the individuals whose lives intersect within them. The rise of the social web demands that if we are to help shape meaningful online experiences for our users, we must rethink our traditional role as builders of digital monuments and turn our attention to the close observation of the spaces that our users are producing around us.