When I started Bearded back in 2008, I’d never run a business before. This lack of experience meant I didn’t know how to do many of the things I’d ultimately have to do as a business owner. One of the things I didn’t know how to do yet? Hiring.

Article Continues Below

When it came time to start hiring employees, I thought a lot about what the company needed to advance, what skills it was lacking. I asked friends for advice, and introductions to people they knew and trusted who fit the bill. And I asked myself what felt like a natural question: would I want to hang out with this person all day? Because clearly, I would have to.

The trouble with this question is that I like hanging out with people I can talk to easily. One way to make that happen is to hang out with people who know and like the same books, music, movies, and things that I do; people with similar life experiences. It may not surprise you to learn that people who have experienced and enjoy all the same things I do tend to look a whole lot like me.

The dreaded culture fit#section2

This, my friends, is the sneaky, unintentional danger of “culture fit.” And the only way out I’ve found is to recognize it for what it is–an unhelpful bias–and to consciously correct for it.

Besides being discriminatory by unfairly overvaluing people like yourself, hiring for culture fit has at least one other major detriment: it limits perspective.

At Bearded, our main focus is problem solving. Whether those are user experience problems, project management problems, user interface problems, or development problems–that’s what we do every day.

I’ve found that we arrive at better solutions faster when we collaborate during problem solving. Having two or more people hashing out an issue, suggesting new approaches, spotting flaws in each other’s ideas, or catching things another person missed–this is the heart of good collaboration. And it’s not just about having more than one person, it’s about having different perspectives.

Perspective as a skill#section3

A simple shortcut to finding two people who look at the world differently is to find two people with varied life experience–different genders, races, religions, sexual orientations, economic backgrounds, or abilities… these factors all affect how we see and experience the world. This means that different perspectives–different cultures–are an asset. Varied perspective can be viewed, then, as a skill. It’s something you can consciously hire for, in addition to more traditional skills and experience. Having diverse teams better reflects our humanity, and it helps us do better work.

This isn’t just my experience, either. According to research conducted by Sheen S. Levine and David Stark, groups that included diverse company produced answers to analytical questions that were 58 percent more accurate.

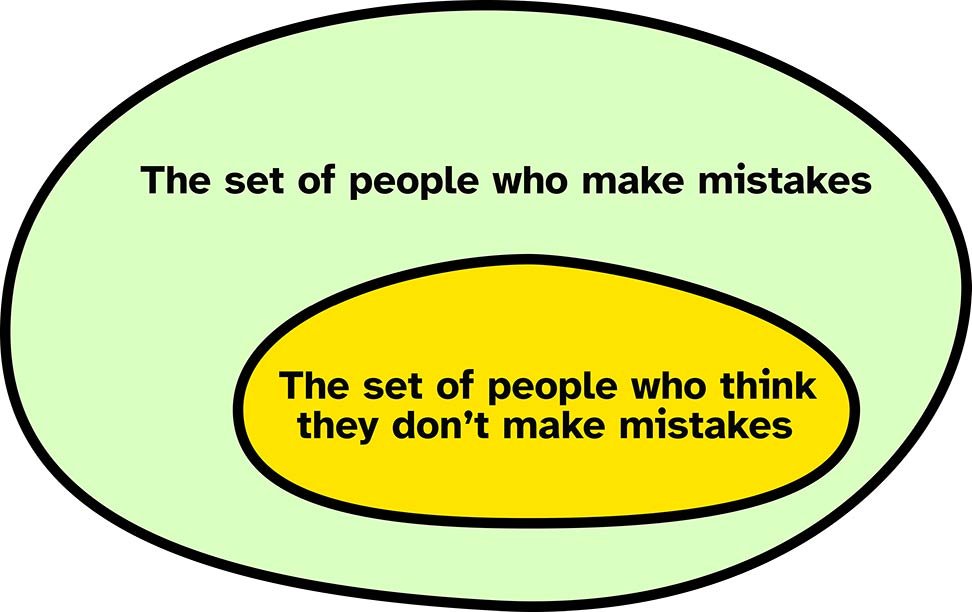

When surrounded by people “like ourselves,” we are easily influenced, more likely to fall for wrong ideas. Diversity prompts better, critical thinking. It contributes to error detection. It keeps us from drifting toward miscalculation.

Smarter groups and better problem-solving sounds good to me. And so does increased innovation. In her article for Scientific American, Katherine W. Phillips draws on decades of research to arrive at some exciting conclusions.

Diversity enhances creativity. It encourages the search for novel information and perspectives, leading to better decision making and problem solving. Diversity can improve the bottom line of companies and lead to unfettered discoveries and breakthrough innovations. Even simply being exposed to diversity can change the way you think.

Phillips isn’t alone in linking diversity to profit. A Morgan Stanley analysis released in May 2016 showed that gender-diverse companies delivered slightly better returns with lower volatility than their more homogenous peers.

Seems like we’d be crazy not to be thinking about building more diverse teams, doesn’t it?

People make the culture#section4

I recently spoke at Web Directions 2016 in Sydney, and was lucky enough to listen to a talk on gender in the tech industry by Aubrey Blanche from Atlassian. Aubrey made a point of how Atlassian has shifted its perspective from finding people who fit their culture, to having a culture defined by its people.

When hiring, this means tossing out the whole “do I want to hang out with them?” question. Instead, I’ve tried to replace that with more specific, more culture-agnostic questions:

- Are they kind and empathetic?

- Do they care about their work?

- Do they have good communication skills?

- Do they have good self-management skills?

If the answer to each of these questions is yes, then it’s very likely I will want to hang out with them all day, regardless of which movies they like.

As Aubrey points out, we can then focus on values, and leave culture alone. Our values might be that we treat each other well, that we do great work that we care about, and that we are largely independent but communicate well when it’s time to collaborate. Then we can also include this new question:

- Do they bring a valuable new perspective?

Hiring based on these values will naturally build a culture that is more comfortable with diversity, because the benefits of diversity become more clear in our daily experiences.

Encouragement and change#section5

Now you don’t need me to tell you no one’s perfect. But when it comes to emotional, high-stakes topics like this, you can see people getting caught in the crosshairs of reproach–and that’s scary to watch. Sometimes it can feel as if we’re all one questionable tweet or ill-considered joke away from public humiliation.

That in mind, let me tell you about a time when I was an idiot.

For context, you should know that I’m a white, heterosexual, cisgender male who grew up in a stable, upper-middle-class environment, and now runs his own business. I pretty much tick all the privilege checkboxes.

Last year at a design conference, I was chatting with industry friends. At some point I brought up a meme that I thought was funny, until one of my friends pointed out that it was sexist. And he was right.

Oh crap, I thought: I’m that guy at the conference, I’m a terrible person. Luckily my friend went easy on me. He understood how I missed the underlying sexist assumptions of the joke, and was happy to bring that to my attention without extending the accusation of sexism to me, personally. He effectively reassured me that I could do something bad, while still being a good person. He gave me the option to admit bad behavior and correct it, without hating myself in the process.

And this, I think, may be the key for people in my very privileged position to change. When problems like this come up, when we make missteps and unveil our biases and ignorance, it’s an opportunity for change. But the opportunity is often much more delicate than any of us would like. Successfully navigating a situation like that requires sensitivity and control from both sides.

For the transgressor, being called out on an issue can feel like being attacked, like an indictment. For those of us who aren’t used to being made uncomfortable, that can be shocking. It can be something we might want to quickly deny, to reject that discomfort. But not all discomfort is, in the end, a bad thing. To give others’ feelings and concerns merit–to validate their different perspective–may require us to sit with our own hurt pride or injured self-image for a bit. Something that may help us through these difficult feelings is to remember that there is a big difference between behaviors and identity. Bad behavior is not immutable. Quite the opposite, bad behavior is often a first step toward good behavior, if we can withstand the discomfort of acknowledging it, and muster the strength to change.

It’s tough getting called out for bad behavior, but things aren’t exactly simple on the other side of the confrontation, either. When we’re offended by someone’s ill-considered words or actions, it can cut to the quick. We might feel required to respond with the full force of our anger or outrage. After all, why should we be expected to police our own tone, when we’re responding to words that weren’t prepared with our feelings in mind? It can be hard, but employing our empathy, our compassion—along with our critique—can be the best way to affect the positive change we want to see.

Right now, you’re doing your best. But we can all do better. Recognizing that we’re doing some bad things doesn’t make us bad people. You have the courage to see what you’ve been doing wrong (unintentionally, I know) and fix that. You can admit to having unfair privileges in the world, without it being your fault for having ended up that way. The world is terribly, horribly unfair. It may very well get worse. But when we have sway, even over a tiny part of it, we have to do our best to balance those scales, and make things a little better. I can do more, and so can you. So let’s see if we can’t get to an even better place in 2017, together.

Many thanks to Aubrey Blanche and Annette Priest for their thoughtful consideration and feedback on this article. My infinite gratitude goes out, as always, to my editor Rose Weisburd, who helped me find my way even more than usual this time around.