If I made a list of the core best practices that have emerged on the web standards front, almost everyone reading this article would understand not only the practices themselves, but also the benefits that have caused these practices to emerge.

Article Continues Below

Here’s my simple list:

- Use structural, semantic markup.

- Separate presentation from the (X)HTML document using CSS.

- Rely on JavaScript as an enhancement for, not a replacement of, website features.

I hear readers of ALA shouting cynically aloud, en masse, “Brilliant Molly! Breakthrough thinking there!”

Seriously, we know by now how structure gives us something to hang our proverbial hats on. And that semantics help make our content more meaningful and therefore more useful and reusable. And yes, we’re all-too-well-aware that CSS helps us keep our (X)HTML documents cleaner, smaller, more streamlined, more manageable and of course, more easily styled.

Naturally, we’ve all been reading about (or even following) best practices for JavaScript and related technologies such as Ajax, JSON and AHAH. It’s become very clear that the concept of unobtrusive JavaScript has become rather obtrusive, and for good reasons: easier document management, encouragement of cleaner, standards-compliant code, accessibility and usability gains.

So what’s gotten me so excited? Well, there is something really interesting that I didn’t begin to explore until just this year, which is how deeply entrenched in markup, CSS, and even JavaScript the creation of internationalized, localized, and multilingual websites really is. We know that crafting a more accessible website relies on understanding

and using web standards including (X)HTML and CSS. It’s interesting to

see how the same practices relate directly to the design and development

of internationalized sites.

The importance of internationalization#section2

While interest in web accessibility has increased over the past several years, another, quieter interest area has been just as important to making sites available to more people. Internationalization is a word most of us have heard, but that few understand.

Internationalization, which is often written shorthand as i18n (first letter, 18 letters, last letter), refers to the practice of designing and developing a product, application, or document in a way that makes it easily localized for target audiences that vary in culture, region, or language.

Internationalization also:

- removes barriers to local and international access,

- provides the technology that facilitates local and international access, and

- provides the technology relating to local, regional, linguistic or culturally-related concerns.

In simple terms, i18n means understanding that the thing you’re designing and developing will be used by audiences around the globe. This is one reason internationalization is sometimes referred to as globalization.

Localization of sites#section3

In order to understand internationalization more completely, it’s essential to understand the concept of localization (or l10n). Internationalization refers to the overarching ideology and mother-lode of technical features that enable us to make sites ready for a wide variety of audiences. Localization, on the other hand, is the actual adaptation of those sites to meet the language, cultural, and other requirements of a specific target market.

Localization is more than translation. Specifically, localization refers to customizing sites to reflect appropriate:

- numeric, date and time formats,

- currencies,

- keyboard usages,

- use of color, and

- sensitivity to cultural perceptions of language, iconography, and imagery.

While internationalization gives us the technology and tools to target a given audience, it’s the act of localization that makes the site accessible to that audience. This is the tricky part, because while some aspects of localization—such as producing a site in languages other than English—involve an understanding of proper markup, the real challenge of localization is understanding the cultural needs of the audience you’re attempting to reach.

Here in Tucson, Arizona, there are a large number of Mexican-Americans. This community is unique in its language, cultural references, and values as expressed in art, music, religion, and ritual. Subgroups within the main demographic reflect even more specific and complex influences based on the economic status, education, and access to resources of the individuals that make up these subgroups.

Imagine that I’m working for a community outreach program that works with a specific group within this demographic to provide educational opportunities, language programs, and community resources.

The world of this demographic is very different than my own—despite our proximity geographically. There are concerns of language—and I don’t mean just translating copy into Spanish! It will be critical that I use the regionalisms, terms, and cultural references specific to the Tucson area, which are going to be different than those of other U.S. cities close to the Mexican border, such as El Paso, which has its own regional and economic influences.

Unless I have significant exposure to the unique aspects of Mexican-American life in Tucson, I most certainly need member representatives from that demographic to help me better understand the sociological significance of the imagery, colors, and other non-technical aspects of the outreach program’s website.

Through the eyes of the standards-aware designer#section4

Now that the meaning of internationalization and localization is more clear, we can begin to understand the relationship between internationalization and localization and the concepts we already use as standards-aware designers.

Structure#section5

When I write of a document’s structure, I’m referring to the building blocks that make up an (X)HTML document. Examples would include a DOCTYPE declaration, root element html, head, title and body elements along with any elements that are there for the structural integrity of the document. Note that this is distinctly different than semantics, which I’ll get to in the next section.

A well-structured (X)HTML document is immediately relevant to internationalization in the context of language. Encoding, while ideally set on the server, may also be present in an XML declaration or meta element as in this case for EUC-JP (Extended Unix Code—Japanese):

Or in this case, 8-bit Unicode (for universal characters)

You can only use lang and xml:lang attributes to designate document language if you’re using structural elements such as the root element of html:

Good structural choices also allow you to designate a change of language within a document. Consider the following sentence, and imagine it being read by a screen reader. Without the clarification that “chat” is in this case, a French word, the device will read it as an English word and pronounce it “chat” as in “we were having a chat”:

The French word for cat is chat.

Other issues, such as bidirectional markup for documents with multiple languages and written in multiple directions (such as a document in English and Hebrew) also fall into this category.

Semantics#section6

A lot of discussion has taken place over the last two years or so about semantics in web markup. There’s also been a lot of confusion over terminology. You’ll hear people say “structural markup” when they mean “semantic markup” and the like. To clarify, when I write of semantics, I’m describing the meaning of something. A semantic element is an element that best describes the meaning of the content it’s being used to mark, rather than describing the way that content should be presented.

In the late 90s, debates about whether em and strong elements being better to use than i and b became a tired constant. At the time, we didn’t use the word “semantic” to clarify the discussion, but now we do, and it’s a lot clearer to us that “emphasize” refers to meaning, whereas “italicize” is presentational.

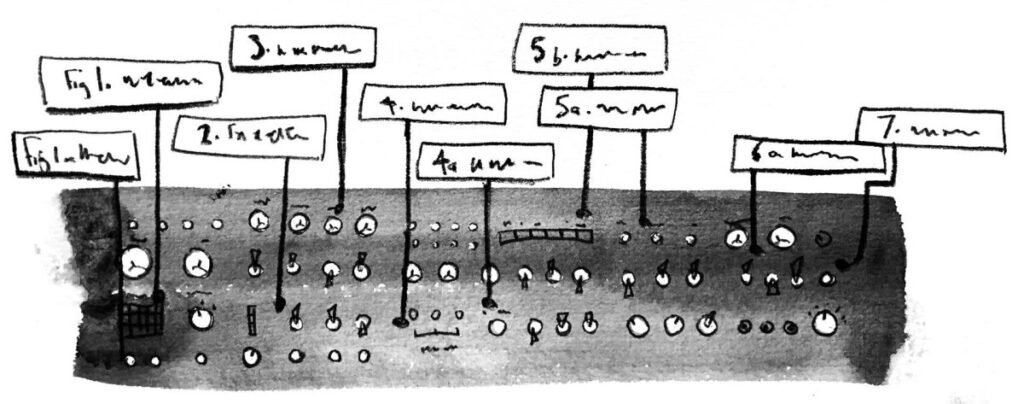

Emphasis is a great example of why semantics are so critical to internationalization. Let’s say the text of my document is in Japanese. Well, Japanese doesn’t always use italics as a form of emphasis, so using tags around ideographic text is quite ridiculous when you think about it. However, using tags around the emphasized content, I can style that content differently. Some methods of visually indicating emphasis, such as a shaded box around the characters, can be done right now with CSS 2; round markings, while currently unsupported, will be available in CSS 3:

Two ways of emphasizing the same line of text.

Image used courtesy Richard Ishida, internationalization Lead, W3C

Semantic naming for class and id values is also important. Choosing names based on function rather than the presentation is, as always, a good practice. In this case, the reason is that a function is far less likely to change during localization than is presentation, which is very likely to change.

One document, many presentation options#section7

It’s back to the old “separate presentation from the document” concept with this one. If you want to create an internationalized and localized site that addresses a number of target audiences, you may have multiple presentation needs. Such needs would include fonts, line-height, emphasis styles, line-wrapping styles, and so on. This is particularly true for languages with accents or non-Latin writing systems.

The next three screen shots display the same document styled in three different ways for three different audiences. You’ll notice differences in color, text location, and even text direction.

Example with both English-language text and Chinese-language text visually emphasized.

Example with English-language text visually foregrounded.

Example with Chinese-language text visually emphasized and English-language text given secondary emphasis.

Images used courtesy Richard Ishida, internationalization Lead, W3C

The W3C’s technologies and techniques create the bulk of what we call

“web standards.” Internationalization makes up a significant piece of

standards, but most of us haven’t focused on internationalization’s role in relation to

standards. The W3C, in contrast, has been working

hard to ensure that internationalization is integrated into the greater

vision. The CSS Working Group, for example, spends a lot of time talking

with the i18n folks to come up with solutions for language styling and

so forth.

While many people around the world work with aspects of i18n and l10n daily, most folks working in web design and development do not. I’m of the firm belief this is about to change dramatically in the next few years, as countries around the world begin to see the web as a clean, affordable, and advantageous technology that can be used to further international efforts.

As our skills in markup, CSS and JavaScript improve, it’s a good

idea for standards-savvy web professionals to begin exploring

the technical and social issues within the internationalization realm.

Check out the excellent resources at the W3C i18n web site, join the W3C i18n Interest Group mailing list, and try out The Web Standards Project. A very special thanks to Richard Ishida, Internationalization Lead, W3C, for his assistance and support.